There were some in France who, in face of even the most alarming statistics, were quick to play down the macabre toll of victims of Covid-19, arguing that in the summer of 2020 the phenomenon was comparable to a bad flu epidemic.

In mid-October last year, when the circulation of the coronavirus was for a second time rising fast, Didier Raoult, a microbiologist and director of the Marseille-based Méditerranée Infection teaching hospital institute and head of its infectious diseases laboratory, told Mediapart: “You’re going to see that the life expectancy will not diminish in 2020, because those who have died from Covid-19 this year have the same profiles as those who died from secondary infection from a rhinovirus or others in 2019.”

That second wave of Covid-19 infections which took hold in France last autumn was followed by a long plateau of numbers of deaths. After a six-week second lockdown, between October 30th and December 15th, came the third wave, which struck earlier this year.

Last Thursday, official figures for the number of deaths in France from Covid-19, recorded since the start of 2020, reached 100,000 – a figure that relates to deaths in hospitals and care homes – and by Saturday this weekend totalled 100,622, according to Santé Publique France, the health ministry’s administration for epidemiological monitoring.

Paradoxically, while the shocking list of fatalities has grown, the importance once given to the public presentation of the daily numbers of deaths has diminished. During the first two-month lockdown that began in mid-March 2020, France’s director general of health, Jérôme Salomon, a civil servant who is in effect the health ministry’s second highest official, gave daily press conferences to solemnly announce the latest data on the epidemic. But now, Salomon, who became sadly nicknamed by some as “the undertaker”, has almost disappeared from public view.

A historic fall in life expectancy in France in 2020

Life expectancy in France fell by six months year-on-year during 2020 for women, a little more for men, whereas the previous trend for many years had been an annual increase in life expectancy of about three months. “Life expectancy is a very stable index,” commented Michel Guillot, a specialist in deathrate research at France’s National Institute of Demographic Studies, the INED. “It has increased almost constantly since the Second World War, and more clearly still since [the end of] the devastating effect of tobacco smoking in the 1970s. In 2020, it saw the biggest fall recorded since 1945. In that respect, Covid-19 constitutes an event never witnessed before, all the more in that the decrease happened despite all the preventive mechanisms put in place.”

“After the first wave [of Covid-19 infections] in 2020, it was possible to think that there would be fewer deaths during the second half of the year, [because] Covid-19 had precipitated the deaths of the most vulnerable,” Guillot added. “We saw this ‘harvest’ effect in 2003 [editor’s note, when a heatwave led to an exceptional number of deaths, mostly among the elderly]. Life expectancy could even have continued to grow, which was the case for men following the heatwave. The second wave of Covid-19, and then the fact that the epidemic is enduring, changed everything.”

Today, Professor Didier Raoult, in response to the suggestion that his forecast was wrong, insists: “There is no second wave, nor a third wave. Each time different illnesses were involved.” However, the symptoms of Covid-19 are very much the same whatever the variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus – the virus behind the pandemic that was fist called “2019 novel coronavirus” and which is the successor to SARS-CoV-1 virus that emerged in 2002.

Above (not reproduced here) : a graph published by France’s national institute for statistics and economic studies, INSEE, which shows a 0.5% drop in 2020 for life expectancy among women (in purple) and a fall of 0.6% for men (in blue). © Mediapart

Close to 80% of those recorded as dying from du Covid-19 in France in 2020 were aged above 75

“Globally, there has not been a comparatively high death rate among people aged under 65,” Raoult argues. “The increase is notable only among over-75s.”

The INED’s Michel Guillot agrees, but with more nuance: “No significant increase [in deaths] is, indeed, observed among the under 50-year-olds during 2020, but as of that age there is a very slight increase linked to a surplus of deaths at periods of peaks in the epidemic. It is accentuated as of the age of 70.”

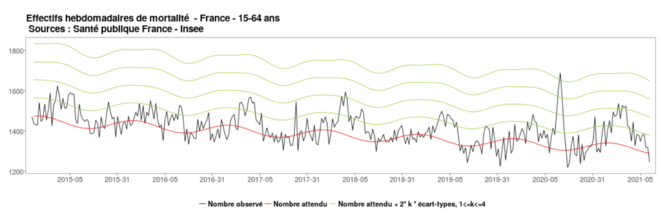

Above: an official graph published by Santé Publique France showing weekly fluctuations in deaths in France among the 15-64 age group. © Capture d’écran Santé publique France

Among all deaths recorded in 2020 in France as having been caused by Covid-19, around 80 % of these were among the over-75 age group, according to Santé Publique France. Inevitably in peacetime, it is the most elderly age group which accounts for most yearly deaths. They represented the first category of victims of Covid-19 but, commented INED research director France Meslé, “only slightly more than for other causes of mortality”.

In its epidemiological bulletin published on March 18th this year, Santé Publique France noted: “In particular, a rise in the proportion of hospitalisations and admissions to intensive care services is observed among young adults.” Possible explanations of this phenomenon are that the most elderly among the population were made the priority in the vaccination programme, or that it is the result of the emergence of new variants of the virus. Or even both.

Despite the increase in the numbers of younger people among hospital admissions, for the time being there has been no increase in the death rate among them. However, future data is needed to confirm this, because there is always a lapse of time between when a patient is admitted and their eventual death.

An increase in the deathrate in 2020 of 9% over recent years

While the death toll from Covid-19 continues to increase in parallel with the virus epidemic, there are those who argue that the victims, or a large number of them, would have died during the same period from other causes. INED researchers France Meslé and Gilles Pison conducted a study of the excess in deaths in 2020 attributable to Covid-19, and which has been widely cited since its publication in March. “Deaths from Covid-19 partly affected fragile people suffering from other diseases,” they wrote. “A section of these would in any case have died in 2020 even without the Covid-19 epidemic. Their deaths would have been attributed to another cause (diabetes, heart disease, chronic respiratory disease).”

It would appear irrefutable that a section of those in poor health would have died of other causes in 2020, given that those most at risk of developing a serious form of Covid-19 are above all the oldest and those suffering from a chronic condition like diabetes or very high blood pressure.

According to France’s national institute for statistics and economic studies, INSEE, there were around 55,000 more deaths recorded in 2020 in comparison with 2019, representing an increase of 9%. “It is possible that for vulnerable people, the arrival of Covid-19 accelerated the advent of cardiac failure, for example if the patient already had comorbidity,” commented France Meslé. “Covid-19 would then have hastened the death which could have soon happened because of the risk factors, and coronavirus constituted an immediate cause.

Above [map not reproduced here] in seven French départements (administrative regions equivalent to counties), the number of deaths due to any cause increased by more than 20% in 2020 compared to 2019. Move your cursor across the départements to see the data. © Mediapart

Debatable: 42,000 extra deaths in 2020 from Covid-19

It is currently impossible to reliably evaluate how many of the French population would have died last year if the coronavirus epidemic had not occurred. Estimates will be possible when France’s national institute for health and medical research, INSERM, publishes its latest study of causes of deaths in the country , for 2020, which it has announced will be published at the earliest in December, and the to compare these with its data on previous years.

However, INED demographers France Meslé and Gilles Pison have estimated that out of the excess number of deaths recorded in 2020 – that is, the higher number in comparison with 2019 – about 42,000 can be attributed to Covid-19. “That figure of 42,000 deaths should suffice as a reply to those who minimise the consequences of the epidemic,” said France Meslé. “It’s historic.”

In reaching that estimate, they took into account the ageing of the population, which increases yearly, and the number of deaths among the elderly which were classified as “natural” over previous years. They found in that projection that, without the arrival of the epidemic, there would have been 13,000 more deaths in 2020 than in 2019. Therefore, in seeking to establish the true number of deaths caused only by Covid-19, that figure of 13,000 can be deducted from the real number of excess deaths last year.

“The assessment should be made for 2020 and 2021, given the continued duration of the epidemic,” said Gilles Pison, associate researcher at INED and a professor of anthropology with the French National Museum of Natural History. “An assessment [of the period] between April 2020 and April 2021 would be even more significant.”

But the difference in the INED demographers’ estimate of 42,000 deaths from Covid-19 in 2020, and the tally of 65,000 recorded by Santé Publique France, raises important questions. The official figures – 65,000 deaths in 2020 and more than 100,000 to date since January 2020 – are of deaths from Covid-19 as reported by hospitals and care homes and institutions. “Many countries are quite conservative in their count of deaths from Covid-19, with these being recognised only after a test is positive, which has led to underestimations,” said Michel Guillot. “In France, there could have been deaths presumed to be from the coronavirus when tests could not be carried out.”

For France Meslé, that would account for relatively few cases. “It is possible that a small number of these deaths were systematically labelled as being from Covid-19 in the EPHADs [care homes], above all at the beginning of the epidemic, when the screening tests were not widespread,” she said. “When a resident [tested] positive for Covid-19 died, those that followed were often recorded as dying from Covid-19 without there being absolute certainty of that. However, that is hardly probable in hospitals. An ad hoc system was put in place and, between PCR tests and MRIs, there is little margin for error.”

But beyond hospitals and care homes, the official toll of 65,000 French deaths from Covid-19 in 2020 does not take into account those people who died in their own homes. Meslé and Pison estimate, using the results of studies in other countries, that these would account for around 5% of deaths linked to the pandemic, and which, when added to the official figures, would bring the total to around 68,000 deaths.

Around 14,000 deaths from flu in recent winters

Above all, Meslé and Pison argue that the higher-than-average death rate in France in 2020 was actually lower than it could have been because of a fall in non-Covid related deaths. The social distancing and disinfection habits adopted because of the epidemic offered protection against other infectious illnesses, such as gastroenteritis and respiratory diseases like seasonal flu.

The latter was less severe and thus less deadly during the winter of 2019-2020 than in previous years, and was estimated by Santé Publique France to have that winter claimed the lives of 3,700 people. That compares with 8,000 deaths from flu in France the previous year, and around 14,000 deaths from flu during the winters of 2017-2018 and 2016-2017. “That shows that the social distancing measures work for flu, an illness that is very much avoidable between vaccination and [direct physical contact avoidance],” said Guillot.

An unknown factor here is whether some of the deaths attributed to seasonal flu during the first two months of 2020 may have in fact been due to Covid-19, which was then only just emerging on official records. Notably, it is now known that the coronavirus had begun circulating in the country as of the autumn of 2019.

But the reverse is also possible.

“With hindsight, in terms of its seriousness, the first wave of Covid-19 was not something absolutely abnormal, but the fact that there were several waves means that there’s nothing that is comparable in recent times,” said Hervé Le Bras, a demographer and historian and director of studies at both the INED and France’s social sciences school EHESS. “You have to go back to 1918-1919 Spanish flu to find a strongly widespread epidemic.”

In an article previously published by The Conversation, Meslé and Pison wrote: “The comparatively high death rate from the autumn wave is significantly superior, even when limited to deaths that occurred in 2020. The peak is less high, but lasted longer. The total toll when including those who died in 2021 already shows itself to be much greater than those for flu epidemics of recent years.”

Between March 10th and May 8th 2020, there were 27,000 more deaths than during the same period the previous year, according to statistics office INSEE.

The deathrate fall during the first French lockdown

The lockdown measures in face of the epidemic also led to a fall of deaths, and including those caused by road traffic accidents. According to the French government’s inter-ministerial road safety observatory , (l’Observatoire national interministériel de la sécurité routière), there were 700 fewer deaths caused by road accidents in 2020 compared with 2019.

But for a clear picture to emerge one must wait for the future results from the INSERM, when suicides, for example, will demand particular attention. “Strangely, in times of war the number of suicides falls significantly, people are focussed on other things than their own ill-being,” commented Guillot. “In the end, [as] everyone was forcefully rested during the first lockdown, that doesn’t mean that the number of suicides increased during the period. However, that could have significantly increased since then.”

Concerning deaths from alcohol abuse, the demographer added: “Alcoholism at home exists of course, but alcohol-induced comas and other accidents linked to excessive consumption of alcohol, like drownings, occur above all outside [the home]. It’s the same for drugs, with a limited access [to them] during the first lockdown. But the toll could very well be reversed with a possible increase in consumption during the rest of the year.”

Meanwhile, a study by academic researchers from France’s school of public health policy studies, published in late April last year (available here in English) found that the first month of the first lockdown may have allowed up to 60,000 deaths from Covid-19 to have been avoided.

In the US, life expectancy dropped by one year according to forecasts made during the first quarter of 2020, and the countries that recorded the most deaths from Covid-19 – importantly, as measured by country and not by size of population – are the US, Brazil, Mexico, India and the UK. For Guillot, “The death rate was particularly high in those countries that did not take strict measures during the spring of 2020, like in the Unites States, Brazil or England”.

But the demographer recognises that, “it is complicated to evaluate the impact of lockdown because numerous factors are at play, such as the health of the population, the quality of the hospital infrastructure, and the system of [health] insurance”.

“Above all,” he said, “the most important thing is age.”

Guillot also underlines that the above-average deathrate in France in 2020 is also a reflection of social inequalities. “In France, immigrants were more exposed, notably frontline workers,” he said. “The risk factors and different medical follow-up can also play a part.”

Sad and revealing data about that from France’s national statistics institute INSEE show that, during the first lockdown in France, from mid-March to mid-May, the deathrate among the population who were born abroad increased by 48% (the report is available in English here). That compared with an increase of 22% for those born in France.

Rozenn Le Saint

Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières

Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook