Two questions were posed to me referring to the views expressed in my previous columns. A couple of weeks ago, commenting on the economic impasse in Sri Lanka, I wrote: “Sri Lanka needs a totally different perspective in order for it to come out of the extant impasse.

The novel perspective should be based on the realistic vision that the Sri Lankan economy should consciously move to what I call ‘low level equilibrium’ oriented towards the needs of the real producers of the society”. People who read the piece queried what ‘low-level equilibrium’ really meant.

Does it mean that the economy has to ride back to a previous level that we had already passed? Does it imply a conscious reduction of the gross national product from its present level? Although it is not a necessary condition, I answer both questions in conditional affirmative; it may.

Let me explain in this piece what is really meant by the low-level equilibrium and how it would affect the living condition of people. The reduction of the former does not necessarily mean the reduction of the latter. At micro level, welfare economic analyses by some well-known economists may support this contention. Associated with this issue and as a solution to the impasse, many economists and bourgeois thinktanks are proposing the Government should go to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for financial assistance.

Knowing very well that the IMF would impose conditionality that the current regime of import controls should be lifted, think tanks have suggested in advance that it is imperative to lift or reduce extant control of imports. Put succinctly, the two questions are: (1) what is meant by low level equilibrium? and (2) should Sri Lanka go to the IMF for financial assistance to come out of the current foreign exchange crisis? Both questions resonate the economic debate in Soviet Russia after the October revolution of 1917. Let me first take the easier question on IMF assistance.

Logic behind mainstream economic theorising

Ceylon Today reported on Monday that the Minister of Finance and the Sri Lankan High Commissioner to India were seriously concerned with the idea of getting IMF assistance. As the paper has also mentioned, key bureaucrats, including the Secretary to the President, The Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka and the Treasury Secretary hold a different position on the issue.

Whether the presence of two opposite views at the centre of power would lead to profound disagreement is yet to be seen. Nonetheless, signs have appeared indicating that there would be a change of positions in order to facilitate the process so that the Government with the Minister of Finance can change track.

What are the arguments justifying the proposal as to why Sri Lanka at this moment should go to the IMF? They are interconnected and intertwined by the threads of neoliberal principles. (1) Theoretically, Sri Lanka would receive around US$ 2700 million in three or four instalments from the IMF if an agreement is signed. Of course, this will cushion up the country’s meagre foreign exchange resources that has been by now dwindled to a level that is sufficient only for one and a half months imports.

As a consequence, the rating agencies would revise Sri Lanka’s credit ratings upwards so that Sri Lanka may raise foreign exchange reserves further by selling in international capital markets Sri Lanka sovereign bonds at a reasonable rate. (2) In addition, placing Sri Lanka by the IMF in its foreign exchange crisis management mechanism would raise the confidence of the investors both local and international to rethink about the future economic prospects in the island.

This may contribute to increase investments. (3) The conditionalities the IMF would impose (rather enforce) would act as necessary corrective mechanisms that include inter alia (a) balanced budget or substantial reduction of fiscal balance (b) liberalisation of trade and capital movements. Both these measures are qualitatively different from the measures that the present Government has been taking since it came to power in November 2019.

IMF conditions

The question to be asked is would the IMF prescription work with regard to increasing growth rate, reducing unemployment and advancing private investments? Let us look at the record. A couple of weeks ago Shiran Illeperuma summarised how IMF prescriptions worked since 2016. “The COVID-19 pandemic hit Sri Lanka at a very difficult period in its economic history. Since around 2012, the country’s GDP growth rate has continuously plummeted, manufacturing output has flatlined, and external debt stocks as a percentage of GNI has reached highs not seen since the mid-1990s.

In 2016, the country entered into an agreement with the IMF to borrow 1 billion in Special Drawing Rights (SDR; an international reserve asset) as part of an Extended Fund Facility (EFF). Policy makers justified this on the grounds that growing debt and flagging growth made an IMF bailout necessary. Predictably, the IMF issued a set of conditions, namely to reduce the fiscal deficit by lowering Government spending and increasing taxation. The currency was devalued. Imports were liberalised. Subsidies on fuel and fertilizer were withdrawn.

Interest rates were jacked up in a bid to rein in inflation. Did it work? Well, the growth rate between 2016 and 2019 (the period of the IMF agreement) declined from 4.5 per cent to 2.3 per cent – the average for the period was 3 per cent. Unemployment rose from 4.4 per cent in 2016, to 4.8 per cent in 2019. Inflation spiked to 7.7 per cent in 2017.

Throughout this period, manufacturing output showed no growth. External debt to GDP continued to increase – fuelled by issuances of international sovereign bonds worth $ 10 billion in these three years alone.” Illeperume’s study reminded me of the Soviet debate between 1918- 1924. In a different context and referring to the changes in the prices of agricultural and industrial goods, Leon Trotsky talked about a ‘scissor’ crisis.

He argued the internal terms of trade behaves in favour of industrial goods, it would discourage peasants to produce surplus negatively impacting the peasants’ production. As a result, scissors would be widely opened.

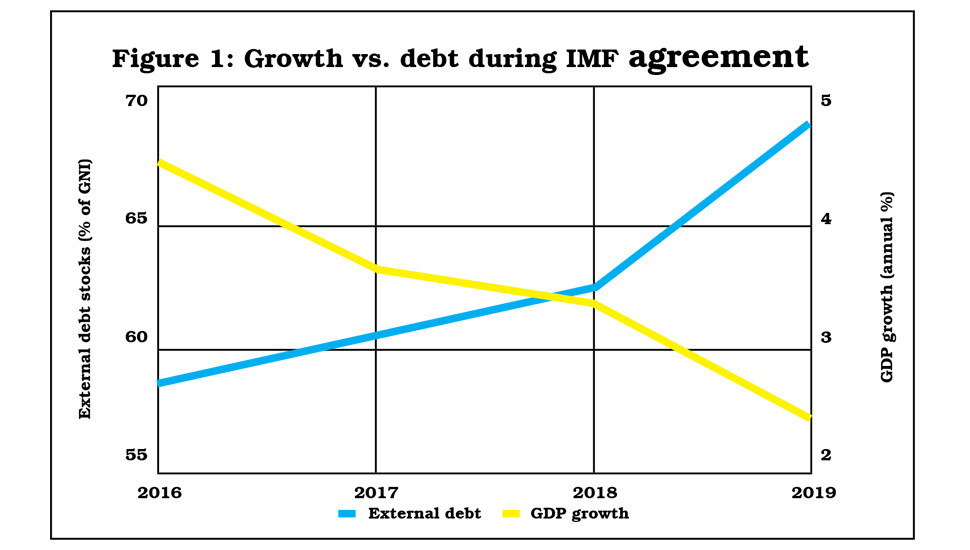

Hence, he proposed a quasimarket mechanism and proposed an imposition of a fixed tax on peasants. Proposal was not accepted. Illeperuma’s diagram (Figure 1) shows that when Sri Lanka increased its dependence on external debt, the rate of growth started to decline. Hence, scissors opened widely showing a negative correlation between increasing external debt and rate of growth.

How do we explain this negative correlation? Debt burden is of course one reason. The fiscal policies adopted by the US during Clinton era shows the stagnant or sluggish growth is partly a result of a balanced budget. This is quite clearly witnessed during the 2018-19 Budgets presented by late Mangala Samaraweera, then Finance Minister. This will bring me to my next point raised at the beginning of the column, low level of equilibrium that was also a part of the Soviet debate in the early 20s especially in the writings of Nikolai Bukharin. I will turn to this issue in the next column.

Sumanasiri Liyanage

Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières

Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook