A revolutionary painter is one who wantonly breaks rules in order to liberate his expression from the bonds of academic art. Why must they do this? In order to create new forms…

George Keyt, Modern Art and the East, Ceylon Observer, June 9. 1963

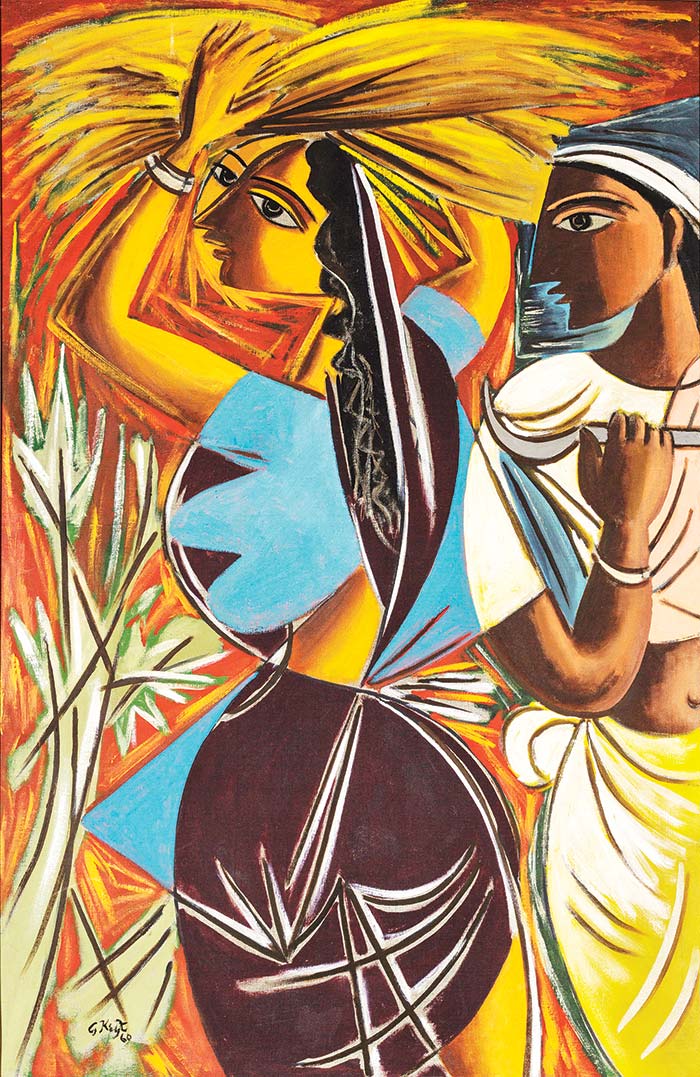

The discovery of Picasso and Braque revolutionized Keyt’s thinking and his painting. Adopting the tenets of Cubism to reshape and reassemble nature, he began to distort form and shape. Breaking up the body, Keyt simplified it into basic geometric forms. Rearranging its appearance, he highlights sharp edges and curvilinear forms to produce multiple intersecting views. Combining cutting lines, sinuous curves and jagged angles, Keyt created his own idea of perspective. Like Picasso, Keyt combined distortion with bold outline, creating oval faces with sharp profiles, often bisecting and dissecting at the same time.

The innovations of modern art made a profound impression in the Ceylon of the 1930s. Its originality, its iconoclasm and its sheer vitality appealed to an emerging generation who were starting to break away from the traditional forms of painting. In 1887 the British administration established the Ceylon Society of Arts. Modeled along the lines of the Royal Academy, it was designed to cater to the wealthy urban and commercial classes who had established themselves during the 19th century. Intended for a group whose social and cultural standards were of the West, the aim of the Society was to “encourage pictorial art” in the colony.

During nearly four centuries of Portuguese, Dutch and British occupation, Ceylonese culture was in eclipse, and the old aristocracy was replaced by a rich urban class whose social and cultural standards were of the West. Colonial education introduced alien standards of art until, in the 19th century, the worst kind of Victorian naturalism became the goal of artistic accomplishment.

William Graham, The Studio Magazine (1954) Dominated by wealthy and influential families who had proved themselves loyal and useful to the British Crown, the Ceylon Society of Arts was a product of the Victorian era, steeped in the conventions of naturalism and representation. Deeply conservative in its attitudes to art, its style reflected the tastes and ideals of the English middle class at the time. The Society had little interest in the artistic traditions of the country and was actively opposed to the developments taking place in contemporary art. All artists had to paint in the style of the reigning British aesthetic. Those who did not were seen as misfits and non- conformists and were rejected.

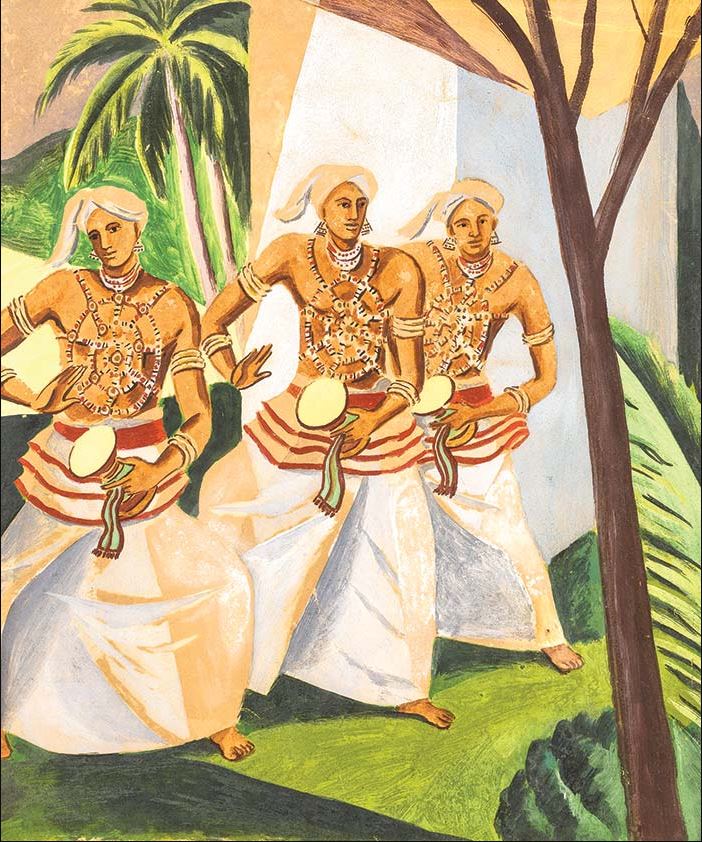

On August 20, 1943, five years before Independence a new, independent group of artists was founded. It was composed of all those who had been excluded by the Ceylon Society of Arts. Known as the 43 Group, it became Asia’s first modern art movement. The 43 Group sought to portray the country’s life, values and traditions in a modern idiom. Inspired by European modernism and the traditional arts of India and Ceylon, the artists agreed to work in their own respective styles, creating, experimenting and interpreting as they saw fit.

The first artistic movement of its kind in Asia, the 43 Group had evolved at a time when both Ceylon and India were still colonies. At a time when modernism was closely associated with change, anti-colonialism and nationalism, the 43 Group generated widespread interest and attention. It also led the way on the Indian subcontinent, where it became the first modernist movement to establish itself.

In the years which followed Independence, the 43 Group held a series of regular exhibitions which gradually established modern art in Sri Lanka. By the early fifties, the 43 Group was winning international acclaim and showing its work in Europe. The 43 Group’s synthesis of traditional forms with modern Western influence attracted widespread praise and comment. In February 1954, William Graham, writing in The Studio, London’s leading magazine of contemporary art, described the 43 Group as “The most significant movement in Eastern Art today.

Breaking with the colonial past, modernism offered a new way of thinking and painting, providing George Keyt with a series of stepping stones, it gave him the opportunity to explore and to experiment, to innovate and to re-invent. Keyt did not avoid these stepping stones. For him, they were merely markers, which enabled him to learn and to grow, to formulate his own visual language and go his own way. Although Keyt had adopted modernism to reinterpret the human form, he did not allow it to dominate or diminish his interpretation. Whereas Braque and Picasso dispensed with line and form, Keyt retained his love of line and outline, maintaining his feeling for the human form.

Once Keyt had rejected Christianity, Buddhism and then Hinduism provided him with an alternative set of beliefs and a way of life. This grounded him in the cultural context of South Asia. In Keyt’s eyes, South Asia possessed what Europe lacked – an ancient creative history and a spiritual tradition of its own. He was too embedded in this reality to allow any set of theories or canons to dominate his vision.

One of the most perceptive analysts of Keyt’s assimilation of modernism was the British civil servant, art historian and curator W.G. Archer (1907-1979). Keeper of the Indian Section at the Victoria and Albert Museum from 1949-1959, Archer was one of the most prominent authorities on Indian art of the time. He came to know Keyt well and featured him in his seminal study India and Modern Art (1959).

Archer was aware that the reproductions of Braque and Picasso had an invigorating effect on Keyt. All of a sudden Keyt realized that he had a “whole new series of idioms ready to hand for conscious adoption.” According to Archer, the example of Picasso helped Keyt discover his own inner consciousness and develop his own style. It offered him a new way of thinking and painting which opened up a way forward. For Keyt, modernism was merely an instrument. “What Europe provided was but a tool, a method.”

The product of a deeply urbanized and colonized culture, Keyt turned his back on the society that he knew. Rejecting the secure, established path he had been destined to follow he embraced the language, art and culture of Sri Lanka’s Sinhala Buddhist civilization, carving out a new identity and life for himself. In the same way that he abandoned the security and stability of his upbringing, Keyt broke with the artistic traditions of his day. In the dying years of the empire, Keyt borrowed, learned and innovated to create anew. Fusing several traditions together, he drew on many cultures and many art forms to evolve a distinct art form of his own. In living the life of his paintings, he transformed himself, as a man and an artist.

Dr. SinhaRaja Tammita-Delgoda

Click here to subscribe to ESSF newsletters in English and/or French.

Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières

Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook